Astronomers Uncover Enigmatic 13-Billion-Year-Old Cosmic Flare, Offering Insights into the Early Universe

A French-Chinese satellite caught something extraordinary in March - a rare gamma-ray burst from a massive star that collapsed nearly 13 billion years ago. This cosmic flash gives scientists a rare window into the universe's early days and how the first stars formed.

The discovery stands out because of its age and precision. Bertrand Cordier, scientific director of the SVOM project at France's Alternative Energies and Atomic Energy Commission, calls it "extremely rare." It's only the fifth most distant gamma-ray burst ever detected, but the measurements are the most accurate scientists have collected so far.

SVOM launched in June 2024 specifically to hunt for these cosmic events. The satellite's full name - Space-based multi-band astronomical Variable Objects Monitor - hints at its mission to spot and pinpoint these powerful phenomena across the universe.

**What makes gamma-ray bursts so special**

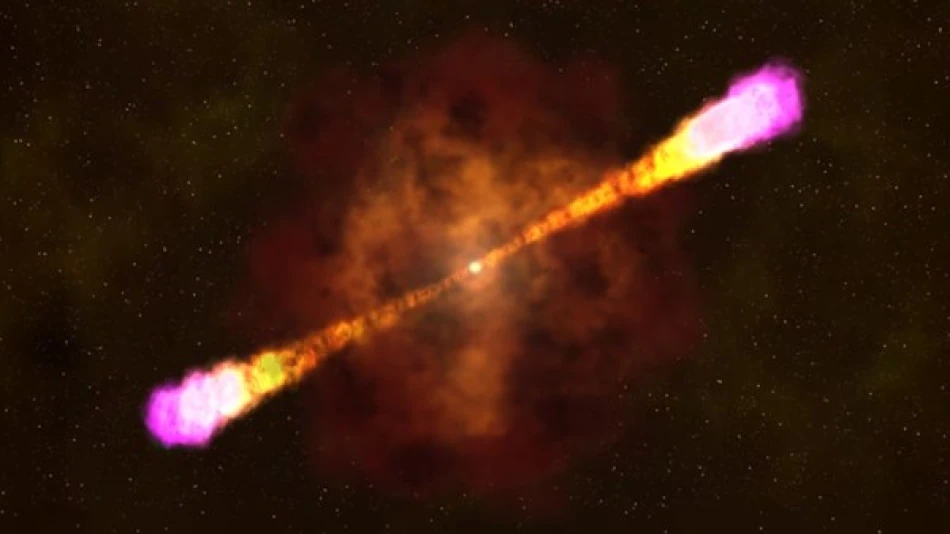

These explosions happen when massive stars - at least 20 times heavier than our sun - collapse, or when dense stars merge together. The energy release is mind-boggling. A single burst can put out more energy than a billion billion suns like ours.

"They're the cosmic phenomena that emit the largest amounts of energy," Cordier explains. He co-authored two studies about this discovery, published Tuesday in Astronomy & Astrophysics.

The physics involved pushes matter to nearly the speed of light. Scientists can't recreate these conditions on Earth, but they can study them through these "cosmic laboratories" in space.

**A probe into the ancient universe**

Here's where it gets really interesting for researchers. These incredibly bright signals work like cosmic flashlights, illuminating all the matter they pass through on their way to Earth. For scientists trying to understand what the universe looked like billions of years ago, these bursts are the only direct method available.

"We desperately need flashes this intense to measure the physical conditions of the universe in very distant epochs," Cordier says. "It's the only way to do it directly."

When the SVOM team got the alert on their phones on March 14, they knew immediately they had something big. They quickly convinced other telescope crews to redirect their instruments toward the burst's location.

This particular burst offers a glimpse of the universe when it was less than a billion years old - a time when the first generation of stars was still forming. The precision of the measurements means scientists can study not just the explosion itself, but the cosmic environment it traveled through to reach us.

Most Viewed News

Layla Al Mansoori

Layla Al Mansoori